We wish to take this opportunity to thank the Ministry of Education (MoE) in funding a radical approach towards English, as expressed in Wave 2 of the Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025.

We hope this funding will continue in Budget 2018 as more schools agree to undertake the Highly Immersive Programme (HIP) and the Dual Language Programme (DLP). It will not be an overnight success nor a fly-by-night exercise but instead, a gradual outcome can be expected as time goes on and confidence grows.

Save for 2016, the total education budget has been maintained at RM54 billion. What is alarming is that of this amount, a mere 10% was — and continues to be — spent on primary and secondary education.

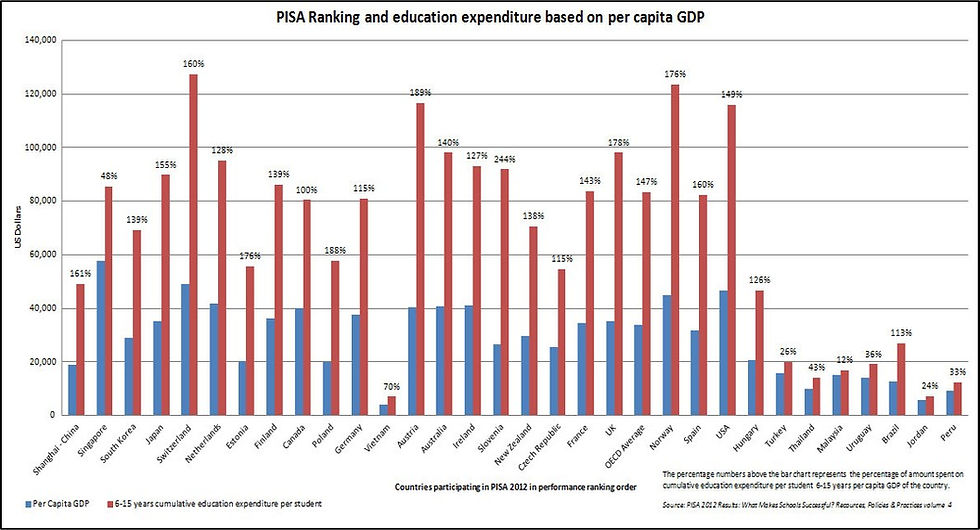

PISA 2012 measures each country’s cumulative spending per student in the 6-to-15 age group (eduex) versus per capita gross domestic product (pcGDP). Eduex is the total amount spent on education per student of that age range for a 10-year period.

Almost all of the performers in the top third spend more than 100% above their pcGDP in eduex. The OECD average is 147%. Malaysia, on the other hand, is at the bottom of the PISA spectrum, spending a mere 12%. Even Thailand, with a lower pcGDP than us, spends 43%, Vietnam is at 70%, while the highest spender is Slovenia, at 244%. However, Malaysia aims to be among the top third by 2025.

It is ironic to note that while Malaysia’s education budget, which allocates an average of 20% of the total, appears generous, it remains low in comparison to the rest of the world. Malaysia’s pcGDP in 2015 was US$26,891. At 12% of its pcGDP, only US$3,227 is spent on the 6-to-15 age group. Based on the OECD average, Malaysia should be spending US$39,530 per student.

We assume there is less cash to spend and that business is no longer as usual. But first, kindly refrain from slashing the budget for primary and secondary schools. Secondly, let us explore how better cost management can make the ringgit stretch further and become more efficient in the short term. Thirdly, if public funding is inadequate, we have to accept that sourcing from the private sector is inevitable, even if it is from the bottom 40% (B40) bracket.

Transparency International Malaysia has remarked that the “Auditor-General Report shows more serious failures in the system due to non-compliance and poor attitude”.

Effectively, it means that contracts awarded to middlemen and rent-seekers at exorbitant prices continue to be subcontracted, leaving little left for the job to be done or, at best, substandard work.

In my own experience, a RM200,000 contract awarded to my child’s school meant providing two coats of paint to the walls of the school hall and another RM200,000 contract got us a small metal roof. After a recent fire at the school office, a contract for RM160,000 was awarded for repairs but a cheque came for RM120,000. A teacher new to a sekolah berasrama penuh (full boarding school) informed me that he was told to approve pillows for students at a cost of RM200 a piece because that is the way it had always been!

The question now is whether we are serious about stamping out wastage, leakages, corruption, or whatever you want to call it. While the immediate reaction would be to make a report to the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC), it is a daunting process. Good citizens should bring justice to taxpayers without fear or favour.

There must be a concerted and conscious effort by all suppliers to exercise reasonableness, integrity and honesty in quoting prices or be forced to face the law. Recipients of goods — be it at the ministry, Jabatan Pedidikan Negeri, Pejabat Pendidikan Daerah or school level, must question inconsistencies, abnormalities and discrepancies.

Broken items supplied should be returned and replaced. Missing items should be reported and replaced. The government should review the amount of the fines as paying for non-compliance may be cheaper than supplying the goods itself. Transform attitude into a conscientious culture.

Return integrity officers to the fore to ensure strict compliance of procedures and processes. Empower them. Make them accessible for complaints to be forwarded, with follow-ups within a strict timeline. Ensure the Whistleblower Act protects.

In times of austerity, be creative in exploring ways and methods to reduce costs, for instance, teachers have to conserve electricity while resources must be shared whenever possible.

Establish a Parliamentary Select Committee for Education to oversee, monitor and ensure responses to the findings of the Auditor-General’s Report and immediate action taken to adhere to recommendations. Investigate and interview persons alleged to conspire to cheat. Empower the committee to initiate court proceedings where applicable.

We do not need to reinvent the wheel — there are already several education models in place or on paper, here and abroad. In all cases, private funding is introduced that put little — if at all any — strain on existing public resources. Key elements of the private system — accountability, parental choice and competition — must be stressed. Our education system should reflect our diversity, which is our strength.

However, the MoE appears to have set a floor price which implies that although viable, such schools cannot charge less than what has been fixed. This should be explored further if we are serious about attracting private funding to the education system in order to bridge the shortfall.

A study on “Private education for the poor in India” is interesting. It looks at schools in Mumbai and Delhi that serve families with very low income, including those living in the slums. Two models exist: affordable private schools that charge a monthly fee (with a voucher system for those who cannot afford anything) and government schools run by the private sector (or even extended to alumni) without charging anything.

The fact that those living in almost abject poverty still choose to pay for quality education is a clear indication that private schools can play a significant role in delivering high quality education to the poor.

In any case, a concerted effort should be made to elevate the teaching profession. Some of the ways include reducing the barriers to entry to keen professionals wanting to be teachers, ensuring their salary scale meets the OECD average based on pcGDP, and offering attractive tax incentives. Also, review the teacher curriculum, raise standards by benchmarking to best international practices and practise meritocracy at all levels to consciously raise the standard of education.

Now, more than ever, with a determined focus on the growth areas of digital technology, bio-economy, nanotechnology and green technology, the acquisition of knowledge and its mastery has never been more acute and critical.